The Comfort of Reality

By Anna Emina El Samad

When I was 17, in the corner of my purple-accented room was a 13-inch Panasonic TV. It sat on

my desk and I would watch every possible program until I fell asleep. My favourite things to

watch were the randomised selection of documentaries that came on every Sunday: recessions,

the history of medicine, investigations into the Titanic and, significantly, all types of programs

about art. It was during one of these quiet Sundays, alone in my room and watching an art

documentary, that an image of Rembrandt’s Carcass of a Beef appeared on the screen. In it a

carcass, mid-butcher, hangs suspended on a wooden beam. It is beheaded and skinned, its

organs removed, the light illuminating the body in Rembrandt's customary style.

I was transfixed by the work. Before me was a dead animal, grotesque, powerless and yet, I felt

a sense of relief. Nothing else could be done now to hurt it . Whatever was to come, being

buried or burned or eaten, would be a mercy to these remains. It reminded me of a line from

Sylvia Plath's poem Edge, “We have come so far, it is over ''. This animal had reached its own

tragic, beautiful edge. It became my favourite painting and I hung a print in my room, to my

mum's horror. I have always been drawn to art that illuminates the feelings inside my head — art

that depicts the uncomfortable truths in our everyday lives. I wouldn't have that feeling about a

painting again until I was standing in the first solo exhibition of Rhys John Kaye looking at a

large oil painting titled ‘Made From Rain’.

The painting hangs high in the open, naturally lit space of At The Above Gallery. In it are two

figures, a solemn woman, overwhelmed by sadness, her eyes downcast, as if on the verge of

tears. Cradling her from behind is an unmasked figure, its hand nailed into position atop her

head. Does the figure represent the woman's thoughts or feelings overcoming her? Is it the

darkness slowly consuming her? Or is the figure a form of comfort, by her side there in the

shadows? Looking at the painting for the first time, I was brought back to the revelation I had at

17, of having something I have felt but never quite understood, visually represented before me.

The painting is a part of a new body of work by Rhys titled “Under The Cover of a Cloud" and

consists of oil paintings, works on paper and sculptures. With the exception of ‘Made From

Rain’, every figure in the exhibition is alone, seemingly in states of emotional contemplation.

Only two of the works depict the subject’s full body — the remaining are displayed from the

waist up, or standing, or sitting, or lying folded on a table, or leaning their head on their hands.

The titles allude to ailments of some kind:, ‘Growing Pains’, ‘The Weeping Man’, ‘Lady Blue’ and

‘Tired of Flying’. The entire exhibition continues like this - dark, full of emotional pain,

confronting.

In focusing on these difficult topics Rhys seems to depict what we would rather ignore. The

feelings of friction, of being still and alone. Despite the many emotions brought up by the work

or perhaps because of this, Rhys is uninterested in providing interpretations for his work, stating

that “if the painting does the right job, then two people looking at the painting will see it in a

different way”. To him, an important element of exhibiting is allowing the viewer to own their

relationship to his work. As our perception of art changes depending on how the viewer is

feeling, so too does how we see things, how we are in the moment of encounter. Rhys prefers

instead to comment on universal themes to describe his work, to start discussions about difficult

topics. Strength, fragility, survival, overcoming and surrender are some of the words I hear him

use.

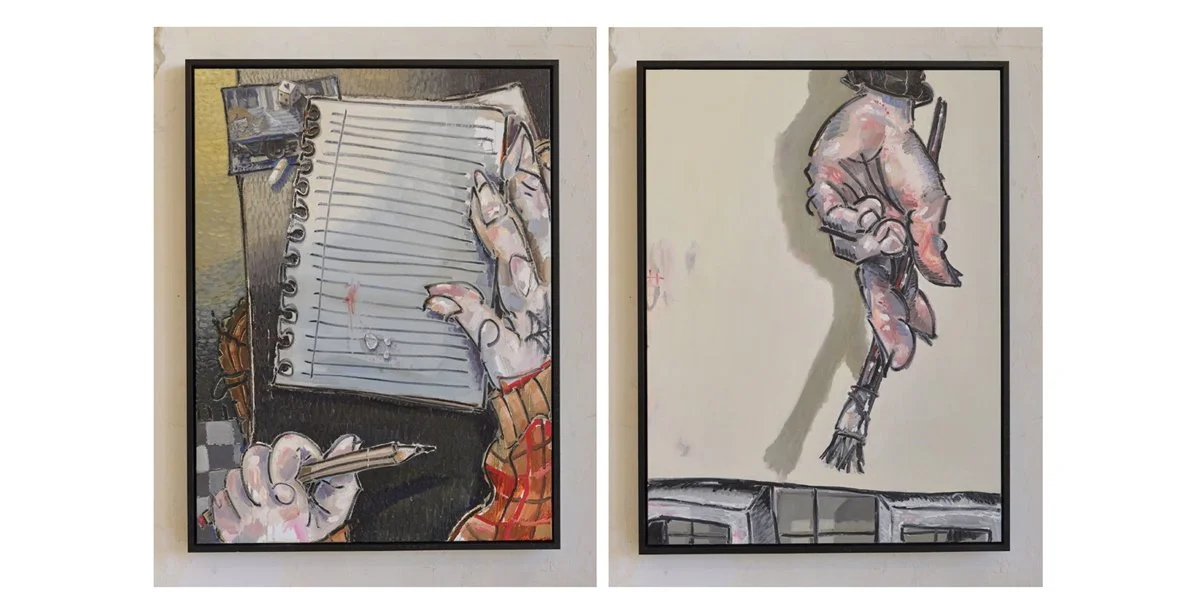

I found myself coming face to face with these feelings of vulnerability and frustration as I stared

into the blank pages depicted in many of his smaller works. ‘Writer’s block’, ‘The Subject’,

‘Paper Study #5 and #9’, ‘Under The Cover of a Cloud’ and ‘Still Life’ all contain the hand of the

artist, brush or pen in hand, floating just above the page. The artist is waiting, trying to create

but there is nothing - the painting just isn't there. As a writer, this feeling - when you are ready to

begin but simply cannot - is all too familiar to me. These works are a visual representation of

that discomfort, the kind you feel when you know you have to start something new, but the

creative impulse has yet to arrive. I often describe writing as pulling teeth, the beginning is

where I battle myself the most, the blank pages a constant reminder of the challenges ahead.

There is an element of needing to face yourself. To come to terms with your feelings when

creating art.

Every time I see Rhys, in his studio or at his residency at At The Above gallery, he is painting or

about to paint or thinking about painting. When I met Rhys at the gallery, he was working on the

very last painting for the exhibition. The diptych canvases were at their beginning stages, having

just been painted in various shades of green - a base for what will become ‘Entering Paradise

Through a Hatch’. The work features a bulky almost mountainous train barely contained within

the canvas. The train seems to be an almost obvious symbol of constant motion, the

continuation and fluidity of life. If not for the skull that appears in the work, merging ominously

with the machine in the background, which transforms the work into something ostensible. It is

at once life and death, forward motion and utter standstill, an encapsulation of the dichotomies

of what Rhys is hoping to achieve and which keeps his audience coming back.

Just days after the opening of his biggest solo exhibition, a culmination of months of work, I

received a message from him letting me know that he was back at work in his studio. I am not

one to glorify the work/hustle culture, pushed by our capitalistic society. But Rhys’s obsession

with art is beyond a need to produce work, it is rooted in unravelling that which is within himself.

He describes it as the need to bring things to the surface, to constantly be in perpetual motion,

like the trains in his works, always moving yet aware of the mortality of all things.

Perhaps Rhys’s most significant strength is his ability to face reality. To see it, understand its

difficulty and still choose to tackle it as his subject. The work appears sad, difficult, emotional,

but here he is saying that we don't have to run from these topics. That strength and fragility are

seen as opposites but can also be the same thing or, as Ai Weiwei discussed, "maybe being

powerful means to be fragile". Sylvia Plath describes the edge as an ending or conclusion.

Here, Rhys has seen the edge and instead views it as the point between the push-pull of life,

between strength and fragility, softness and power, the viewer and the artist.